A rather commonplace early season evening game in Edinburgh between two Championship sides battling to reach the quarter-finals of the 2016/17 edition of the Scottish League Cup carried a much wider international significance than the chance to play Rangers in the next round.

At the last World Cup, 137 players represented countries in which they weren’t born, and this match between Hibernian and Queen of the South encapsulated the growing trend of this practice of “flag of convenience” footballers, featuring two players who would go on to have remarkable autumns six years later playing for countries they had to be persuaded to turn out for.

In only his second senior match and scoring his first ever senior goal for the visitors was a relatively late starter in professional football, Queen’s left winger, the 20-year-old Lyndon Dykes, while the home side featured promising striker and Scotland Under-21 regular Jason Cummings. His club had just turned down a £1.2m offer from Peterborough United but their leading scorer for the previous two seasons couldn’t make the difference for his hometown team this time, Hibs eventually losing 3-1. At the end of the season Cummings had his own significant moment against Dykes, winning his first league winner’s medal in a 3-0 victory against the Doonhamers.

At this stage in their careers, the players’ projected trajectories would have had Cummings playing for Scotland – which did occur for 12 minutes over two friendlies – and Dykes, who had only played semi-professional lower league football in his native Australia, not expected to be playing international football in either southern or northern hemispheres any time soon. Yet Dykes’ sporting career has been defined by large transitions, from rugby league to football, provider to goalscorer, Surfers Paradise Apollo to Queen’s Park Rangers, Australian to Scot – each move bringing him greater sporting, and financial, success.

"The ball rolling in that goal was the slowest thing I've ever seen in my life" 😂

Hear from goalscorer Lyndon Dykes after Scotland secure a dramatic 2-1 victory in Norway 🏴⚽️⤵️

#BBCFootball pic.twitter.com/1QNrdQcgyv

— BBC Sport Scotland (@BBCSportScot) June 17, 2023

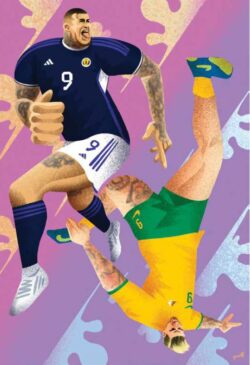

Dykes followed a broadly similar career path to his Championship rival, the Australian native lagging behind the Scot by a few years. Cummings went from English Championship to Scottish Premier League, while Dykes played in Scotland’s top division first for a few seasons before reaching the English Championship then receiving his first Scotland cap, three years after Cummings. The heavily inked 27-year-old strikers, who were born only a few months apart, also responded similarly when asked to play for the country of their mother’s birth, by saying no. It would have been fascinating to see Dykes’ reaction at his old Scottish Championship opponent coming on in the gold of Australia to play against France in the World Cup; trying, and failing, to swap jerseys with Kylian Mbappé.

A few years ago, I wrote a piece for this magazine heavy on conjecture about what conditions would have to be in place for players who identified as English to choose to play for Scotland, imagining a graph where one axis mapped the career path of a player who had the choice to play for Scotland or elsewhere, while the other axis charted Scotland’s fortunes.

The intersection point would be where the player who had been pursued long-term by a Scotland manager became the “I’ve always felt Scottish in my blood” full internationalist. The conjecture was necessary as Scotland’s fortunes were flatlining three years ago, reducing the number of non-native players willing to throw in their lot with us. (Even a suspiciously high number of players who were Scots-born didn’t seem keen to play, judging by the number of call-offs as the international break came around.) In my original piece, Steven Caulker and Angus Gunn were examples of players who qualified for but were uncommitted to Scotland. In the intervening years, while the national team’s fortunes have improved exponentially, the former has been left behind while the latter has joined a group of others recently pulling on the blue, or in Gunn’s case the yellow, jersey for the first time.

Gunn first rejected a chance to play for Scotland five years ago, a few months before he moved from Manchester City to Southampton for around £13m. As a goalkeeper he would have felt confident of being picked for his first-choice nation – the four current English-born English Premier League keepers have all represented their country at senior level – if he could have stayed as the number one at St. Mary’s. Then as Gunn dropped down a division with Norwich City, he reached the level of his “second” country, while conveniently being convinced to play for Scotland by team-mates and new fellow countrymen Grant Hanley and Kenny McLean, coinciding with Craig Gordon becoming a long-term injury casualty.

Gunn’s journey north adds to the intrigue surrounding Brighton & Hove Albion keeper Jason Steele; he has only played a handful of first-team games this season but briefly usurped regular stopper Robert Sanchez’s position. A few more appearances might see him called up by Gareth Southgate for the next round of internationals. However, a loan move to the Championship could be the prompt for him to choose Scotland through the grandparent qualification rule.

Gunn is the 56th player over the past century and a half who has chosen to do so since Arthur Kinnaird, the 11th Lord Kinnaird, born in Kensington but of Perthshire landed gentry, played three out of Scotland’s first ever five games. The trend has been growing over the last few years, with seven in the current squad in the same category. I have personally heard anti-English abuse aimed at both Liam Cooper and Scott McTominay from the Hampden terraces in the recent past. These racist incidents seem to be less frequent now, perhaps with the grudging acceptance from the clueless that you don’t need an accent to be Scottish.

If Scotland were now to field an 11 who didn’t initially identify as Scottish, would this be seen as a watershed moment like the Old Firm first fielding a team of “foreigners” in the 1990s? Two thirds of the Moroccan squad at the last World Cup weren’t born in the North African country that reached the semi-finals, with players from Spain, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands surpassing the traditional footballing heavyweight countries of their birth.

Coincidentally, 56 is also the number of Scots-born people who have played for Australia – including Martin Boyle, who also played in that League Cup game for Hibs against Queen of the South – with one other current player looking like this generation’s “one who got away”, a Ray Houghton for the 21st century. Harry Souttar’s choice of Australia is part of the trend for brothers to play for different countries, highlighting how pragmatic a decision it is for many to choose a nation; after all, I don’t imagine that the Souttars were exposed to different types of nationalism growing up, little John wearing the See-You Jimmy hat at Hallowe’en while Harry dressed as Crocodile Dundee.

Harry’s choice came too early in his career for Scotland to have even considered him for an international call up – the then 20-year-old was on loan at Fleetwood Town in League One at the time, but was frustrated at the lack of Scottish international recognition at Under-21 level. And while the £15m Leicester City paid for him might well make him the most expensive centre-half born in Scotland, that fee was created through his World Cup performances where he excelled against France and Argentina rather than the injury-blighted 101 minutes he experienced over the rest of 2022 with Stoke City. It’s extremely unlikely, bordering on preposterous, that he would have commanded such a fee had he remained Scottish.

Souttar Junior seems to be swimming against the current tide though, which is likely to keep flowing in Scotland’s favour. The more we improve, the more likely Scottish blood is going to be discovered in what is the closest thing to a transfer market in international football, thereby improving Scotland further. It’s a shame no one was on the ball around two centuries ago to sign up the ancestors of Argentinian Alexis Mac Allister.